Donald Bradman

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Sports and games people

Sir Donald George Bradman, AC ( August 27, 1908 — February 25, 2001), often called The Don, was an Australian cricketer who is universally regarded as the greatest batsman of all time, and is one of Australia's most popular sporting heroes. His Test batting average of 99.94 is by some measures the greatest statistical performance of all time in any major sport. By way of comparison, the second, third and fourth best Test averages are 76.56, 60.97 and 60.83. This disparity between the best and the second best exceeds that in other sports, and suggests that Bradman may be considered the greatest athlete of all time.

Cricket career

Early years

Born in Cootamundra, New South Wales, but raised in Bowral (where the Bradman Museum and Bradman Oval are located), Bradman practiced obsessively during his youth. At home he invented his own one-man cricket game using a stump and a golf ball. A water tank stood on a brick stand behind the Bradman home on a covered and paved area. When hit into the curved brick stand, the ball would rebound at high speed and varying angles. This form of practice helped him to develop split-second speed and accuracy.

After a brief dalliance with tennis he dedicated himself to cricket, playing for local sides before attracting sufficient attention to be drafted into grade cricket in Sydney at the age of 18. Within a year he was selected for New South Wales, and within three years he made his Test debut.

Pre-war

After receiving some criticism in his first Ashes series in 1928–1929 he worked to remove perceived weaknesses in his game, and by the time of the Bodyline series he was without peer as a batsman. Possessing a great stillness whilst awaiting the delivery, his shot making was based on a combination of excellent vision, speed of both thought and footwork and a decisive, powerful bat motion with a pronounced follow-through. Technically his play was almost flawless, strong on both sides of the wicket with only his sternest critics noting a tendency for his backlift to be slightly angled toward the slip cordon.

In the English summer of 1930 he scored 974 runs in only seven innings over the course of the five Ashes Tests, the highest individual total in any Test series before or since. Bradman himself rated his 254 in the second Test at Lord's as his best ever innings. His 334 in the third Test at Headingley, of which he scored a Test record 309 runs on one day, was then the highest individual score in Test cricket (surpassed by Walter Hammond in 1933 but not equalled by an Australian batsman until Mark Taylor declared with his score at 334 not out in 1998, in what many regard as a deliberate tribute to Bradman; Matthew Hayden subsequently broke the record, scoring 380 in 2003).

Bradman so dominated the game that special bowling tactics, known as fast leg theory or Bodyline, regarded by many as unsporting and dangerous, were devised by England captain Douglas Jardine to reduce his dominance in a series of international matches against England in the Australian summer of 1932–1933. Orthodox leg-theory was first used in English cricket as far back as 1910 principaly as a run restricting technique bowled by slow bowlers. Jardine's take on this proven idea was to use two fast bowlers, Larwood & Voce, in tandem to bowl at leg stump whilst pitching the ball short - effectively bowling at the batsman rather than the stumps, hence the name given to the tactic by the Australian media, Bodyline. The principal English exponent of Bodyline was the Nottinghamshire pace bowler Harold Larwood, and the contest between Bradman and Larwood was to prove to be the focal point of the competition. Some indication of his superlative skill was that his average for that series, 56.57, is still higher than the career averages of all but a dozen or so international Test cricketers. Due to a dispute over his newspaper reporting role, he missed the 1st Test.

Further evidence of his supreme athletic skills was revealed when Bradman missed the 1935–36 tour to South Africa due to illness. During his absence from cricket, Bradman took up squash to keep himself fit. He subsequently won the South Australian Open Squash Championship.

Jack Ledward, a Victorian batsman, recalls Bradman's footwork in a descrption of a pre-WW II innings played by the Don against Victoria. After playing himself in, Bradman confidently announced that he was about to conduct "a round-up". Ledward watched in amazement as Bradman hit each ball of every over to every fielder in anti-clockwise succession — starting with Ledward at slip and concluding with fine-leg, disregarding the line and length of each individual delivery .

Despite occasional battles with illness, he dominated world cricket throughout the 1930s, and is credited with raising the spirit of a nation suffering under the privations of the Great Depression.

Post-war

Approaching forty years of age, he returned to play cricket after World War II, leading one of the most talented teams in Australia's history, despite being at an age at which most cricketers are long retired. In his farewell 1948 tour of England the team he led, dubbed " The Invincibles", went undefeated throughout the tour, a feat unmatched before or since.

Bradman emerged for what was his last Test innings, at The Oval, with his Test batting average above 100. He needed only 4 runs to keep it in three figures, but he was dismissed for nought (in cricketing parlance, "a duck") by spin bowler Eric Hollies. Applauded onto the pitch by both teams, it was sometimes claimed that he was unable to see the ball due to the tears welling in his eyes, a claim Bradman always dismissed as sentimental nonsense. "I knew it would be my last Test match after a career spanning twenty years", he said, "but to suggest I got out as some people did, because I had tears in my eyes, is to belittle the bowler and is quite untrue." He was given a guard of honour by the players and spectators alike as he left the ground with a batting average of 99.94 from his 52 Tests.

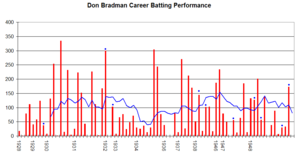

Statistical assessment

Over an international career spanning 20 years from 1928 to 1948, Bradman's batting achievements are unparalleled. His career statistics are far superior to those of any other batsman, and a testament to his unusual powers of concentration. He broke scoring records for both first-class and Test cricket. The final batting average achieved by Bradman was, famously, 99.94. This record (approximately 65% higher than that achieved by anyone else) was the product of a career of astonishing consistent high scoring and a final, ironic incident of rare failure.

Creation of the statistic

Toward the end of a phenomenal, record-breaking career, Bradman came to the wicket at The Oval for what turned out to be the last time in a Test match against England in 1948. It was known that he would not play in England again and the England side (and crowd) gave him three cheers.

At the time, Bradman had scored 6,996 runs in Test cricket from 79 innings, with 10 not outs. His average was thus 101.4 and a score of just 4 would give him an average of exactly 100, having scored 173 not out in the first innings of the match. In his second innings, however, he was bowled by a Eric Hollies' googly for a duck (0).

This failure left Bradman with an average of 99.94 and, although it was not clear at the time that it was his last match, (merely his last in England) he did not play Test cricket again.

A story quickly gained currency that Bradman was unable to see the ball due to tears in his eyes. Wisden itself in its match report (1949) states "Evidently deeply touched by the enthusiastic reception, Bradman survived one ball." (Wisden 1949, pub. Unwin Bros., p.252)

Bradman himself dismissed this; "I knew it would be my last Test match after a career spanning twenty years but to suggest I got out as some people did, because I had tears in my eyes, is to belittle the bowler and is quite untrue."( )

Context

In a sport that revels in statistics, the figure 99.94 has become one of cricket's most famous, iconic statistics.

Contextualising Bradman's achievement is easier than is usual for comparisons of cricket statistics across the eras. Compared to his average of almost 100, no other player who has played more than 20 Test match innings has finished his career with a Test average of more than 61 (see the list of highest Test career batting averages).

Bradman scored centuries at a rate of better than one every three innings. He converted very nearly a third of his centuries into double hundreds, and his total of 37 first-class double hundreds is the most achieved by any batsman. The next highest total is Walter Hammond's, who scored 36 double hundreds but played in exactly 400 more matches than Bradman's 234.

For decades, Bradman was the only player to have scored two Test triple centuries (both against England at Headingley, 334 in 1930 and 304 in 1934). This feat was equalled by West Indian Brian Lara in 2004 (Lara has, however, played more than twice as many Tests). Bradman very nearly reached 300 on another occasion, his last partner being run out when he was on 299 not out against South Africa in 1932. Bradman, Lara and Bill Ponsford are the only players with three first class scores of over 350.

In a biographical essay in Wisden, he is hailed as "the greatest phenomenon in the history of cricket, indeed in the history of all ball games".

In The Best of the Best, statistician Charles Davis argues that Bradman's performance is the most dominant of any player of any major sport. He calculates the number of standard deviations above the mean that several prominent individual sporting statistics lie. The top performers in various sports are:

| Athlete | Sport | Statistic | Standard deviations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bradman | Cricket | Batting average | 4.4 |

| Pelé | Soccer | Goals per game | 3.7 |

| Ty Cobb | Baseball | Batting average | 3.6 |

| Jack Nicklaus | Golf | Major titles | 3.5 |

| Michael Jordan | Basketball | Points per game | 3.4 |

| Björn Borg | Tennis | Grand slam titles | 3.2 |

In order to post a similarly dominant career statistic as Bradman, a baseball batter would need a career batting average of 0.392, while a basketballer would need to score 43 points per game.

Personal

Bradman married his childhood sweetheart Jessie, and they had three children, Ross, John and Shirley. Ross died only 36 hours after birth. Jessie died in 1997. Bradman, an intensely private person, was regarded as aloof even by team-mates, particularly in later years. A strict adherent to the Church of England, he had occasionally been accused of anti-Catholicism in his actions as captain and selector, but this was against a background of widespread sectarian prejudice in Australia.

Despite his sporting abilities, Bradman was declared unfit for service in the Second World War, and was spared the dangers of fighting for King & Country.

He spoke out against smoking in sport, which was very unusual for the time. His books on cricket technique and tactics are regarded as classics.

After cricket

After retiring from playing cricket, Bradman continued working as a stockbroker. Allegations that he had acted improperly during the collapse of his employer's firm and the subsequent establishment of his own, made behind closed doors until his death, were publicised in November 2001. He became heavily involved in cricket administration, serving as a selector for the national team for nearly 30 years. He was selector (and acknowledged as a force urging the players of both teams to play entertaining, attacking cricket) for the famous Australia–West Indies Test series of 1960–61.

As a member of the Australian Cricket Board, and, reportedly, their de facto leader, he was also involved in negotiations with the World Series Cricket schism in the late 1970s. Ian Chappell, former Test captain and selected to lead the rebel Australian side, has stated that he places much responsibility for the split on Bradman, who in his opinion had forgotten his own difficulties with the cricket authorities of the time.

He was also famous for answering innumerable letters from cricket fans across the world, which he continued to do until well into his eighties. Bradman died in 2001, in Adelaide, aged 92.

Honours

Bradman was selected as one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1931. He was awarded a knighthood in 1949, and a Companion of the Order of Australia (Australia's highest civil honour) in 1979. In 1996, he was inducted into the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame as one of the ten inaugural members.

In 2000, Bradman was selected by a distinguished panel of experts as one of five Wisden Cricketers of the Century. Each member of the panel selected five cricketers, and Bradman was the only player to be named by all 100 correspondents. The other four cricketers selected for the honour were Sir Garfield Sobers (90 votes), Sir Jack Hobbs (30 votes), Shane Warne (27 votes) and Sir Vivian Richards (25 votes). Some members of the panel commented that two of the five votes cast would be effectively wasted, as they had to be cast for Bradman and Sobers. In 2002, the Wisden rated Bradman as the greatest ever Test batsman. Tendulkar, Gary Sobers, Vivian Richards were placed at 2nd, 3rd and 4th positions respectively. Bradman's innings of 270 in the third Test against England at the Melbourne Cricket Ground was rated by Wisden as the greatest ever Test innings.

Trivia

Bradman is immortalised in three popular songs of very different styles and eras, "Our Don Bradman", a jaunty 1930s ditty by Jack O'Hagan , "Bradman" by Paul Kelly in the 1980s, and in "Sir Don", an emotional tribute by Australian Singer John Williamson at Bradman's Memorial Service.

The story of the Bodyline series was embroidered in a 1984 television drama mini-series in which Hugo Weaving played Douglas Jardine and Gary Sweet played Don Bradman.

The name "Bradman" is now protected in Australia, in that it cannot be used as a part of a trademark except for government-approved institutions linked to Donald Bradman.

A main arterial road in Adelaide, South Australia, formerly Burbridge Road, was renamed Sir Donald Bradman Drive.

An often repeated story is that General Manager of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and personal friend Sir Charles Moses asked that Bradman's Test batting average be immortalised as the post office box number of the broadcaster - "Box 9994 in your capital city". There is some debate about this, but ABC sports host Karen Tighe confirms that the number was in fact chosen in honour of Bradman , and the claim is also supported by Alan Eason in his book The A-Z of Bradman.

Bradman played in several nations but never actually played on Australia's next door neighbour New Zealand's soil

After Bradman passed away, the Australian Government produced commemorative 20 cent coins.